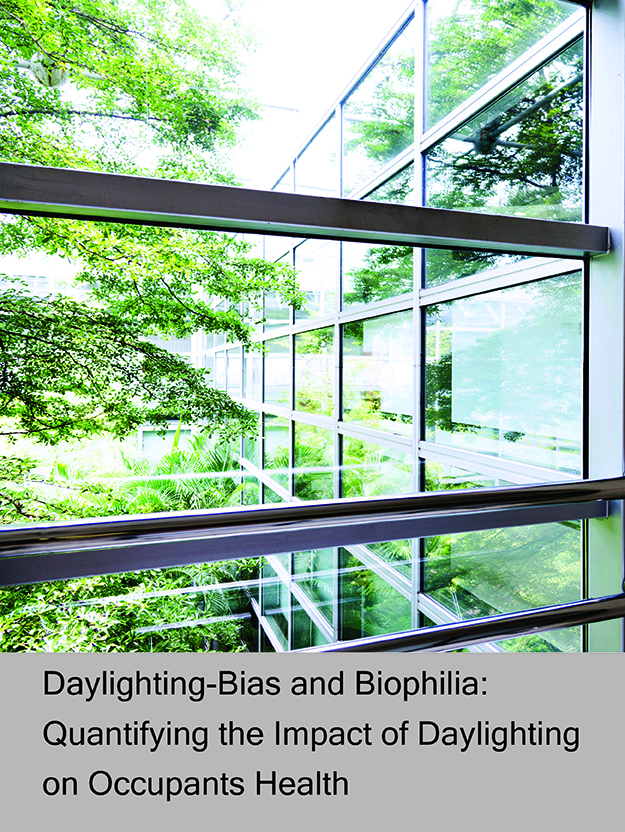

Daylighting-Bias and Biophilia: Quantifying the Impact of Daylighting on Occupants’ Health

This paper reports on a state-of-the-art study quantifying the health and human impacts of daylighting strategies and views quality from windows on employees health in offices. The study attempts to quantify an important yet not scientifically proven assumption concerning the biophilic relationship between views of nature and daylighting in the workplace and their impacts on sick leave of office workers. The specific hypothesis tested is; that employees with a view of nature will take fewer sick days, have fewer Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) symptoms than those with a view of urban structures, or with no views out at all. A corollary hypothesis is whether daylight availability and dynamic lighting quality in offices could also play a role in reducing the number of sick leave hours and SBS symptoms related to poor circadian rhythms and hypersensitivity. This is an objective to answer and quantify a long debated hypothesis regarding the importance non-residential building occupants place on the need to be in contact with nature/the outdoors while working within a building. This paper reports on a three-phase long-term study. In phase I, employees’ preferences and ratings towards natural and urban human-made views were investigated. For this phase of the study a qualitative sorting task technique was employed, followed by in-depth interviews on a cross-sectional sample of office employees (n=98). In phase II of the study, physical office conditions, lighting qualities, and quantities inside120 office spaces and cubicles in an office building were systematically evaluated covering 175 employees participating in this study. This included daylighting availability (window shape, properties, glazing properties, area, and its distance from employees’ desks); Daylighting quality (luminance, glare analysis, room materials, reflections, orientation, brightness patterns, etc.), and quality of outside views (type of view, pleasantness rating, and preference rank) according to the view metric developed earlier in phase I of the study. In phase III of the study, employees’ health conditions were surveyed using an on-line questionnaire and physical health screening forms. In addition, we compiled employees’ actual sick leave days from their payroll records as well as in aggregate format based on their office locations, views, floor level, and area of the building they occupy. A multi regression and Pearson correlation statistical analyses tests were performed on the data set. Standard bivariate regression and correlation were used to examine the relationship between sick leave hours and ratings of lighting quality and views. In both cases, the relationships are in the predicted direction and statistically significant supporting positively our hypothesis. Workers in offices with poor ratings of light quality and in offices with poorer views used significantly more sick leave hours. Taken together, the two variables explained 6.5% of the variation in sick leave use, which was statistically significant. The implications of these findings are huge when one considers productivity and health insurance costs these sick leave hours can affect to an organization.